Aldea Computer: Building the greatest blockchain no one has ever heard of

A case study in challenging blockchain orthodoxy, developer experience, and the reality of ambitious technical projects.

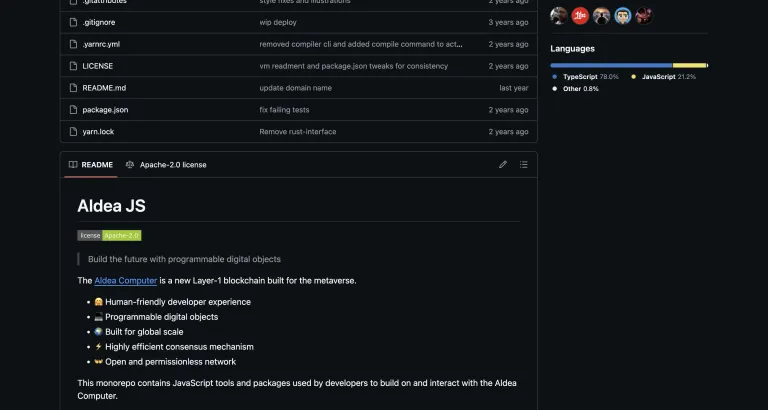

The Aldea Computer was a distributed computing platform designed for simplicity, accessibility, and global scale. I was a co-founder and core member of a small development team, involved in all aspects of the product’s design and technical direction, and primarily responsible for Aldea’s compiler and TypeScript SDK.

Work on Aldea started in the summer of 2022, and in just 18 months the team made some remarkable technical progress. We created a programming model that would stand out today as the most intuitive and accessible in the blockchain space, and we demonstrated a transaction processing model capable of handling tens of millions of transactions per second. But all of this happened in the wake of the FTX collapse and a brutal investment climate. Funding for Aldea ran out at the end of 2023, before we could bring the product to market.

This case study explores the ideas and vision behind the Aldea Computer, the technical work we undertook, what we achieved and what we didn’t, and reflects on the lessons learnt.

The vision: Blockchain for everyone

From the outside, the blockchain space has always been… a bit weird. From day one, Bitcoin’s earliest adopters – cypherpunks and libertarians – baked in a political ideology that valued privacy, individual sovereignty, and decentralisation above all else. On top of that, the core technologies that define a blockchain – cryptography, peer-to-peer networking, consensus – are inherently non-trivial, with a demanding learning curve.

This blend of cypherpunk ideology and crypto technology has always attracted a certain type of person to the blockchain space – including some colourful characters, and plenty of very capable cryptographers, mathematicians and computer scientists. But arguably, this has been at the expense of more product-focussed minds - the communicators, designers and UX professionals of this world.

Consequently, blockchain has become a space where conversations focus more on obscure cryptographic concepts than real-world applications, and where overtly complex solutions to simple (or nonexistent) problems are prevalent. This results in a kind of technical elitism that excludes enthusiasts and everyday developers from participating in the technology, and impacts how the general public relates to the space.

The Aldea philosophy

Aldea’s philosophy was one of simplicity and pragmatism. We weren’t afraid to question blockchain dogma, and we were sceptical of what we saw as a lot of boondoggle technology. Decentralisation was a means to an end, not the end itself. We believed a layer-one blockchain could achieve global scale – handling millions of transactions per second with low fees – whilst remaining “decentralised enough” in all practical senses.

We also believed the technology should be accessible to a much wider developer base. We favoured a simple, object-oriented computing model, with familiar languages and developer tooling. We took a lot of inspiration from the success of the web and from the home computer ethos: we wanted enthusiasts and bedroom developers to be able to pick things up quickly, experiment with fast and cheap transactions, and just have fun.

From Run to Aldea

Aldea’s story doesn’t start in 2022. All of the founders had been involved in Bitcoin and blockchain for some years, and had been drawn to the fresh energy that emerged in the Bitcoin space following the block size hard forks in 2017 and 2018 (initially BCH, and later BSV).

In 2018, Brenton Gunning began working on what became Run – a layer-two token protocol that used JavaScript to create interactive digital objects stored on-chain. Brenton had some success with Run: he secured investment and a number of businesses began building on top of it. During 2020-2021, the Run network was processing some seriously impressive volume – at times handling more transactions than the entire Ethereum network.

I joined the Run team at the beginning of 2022 and was excited to help, but it quickly became clear that Run was in trouble. The enthusiasm for big-block Bitcoin from 2017 had evaporated – the space was beset with infighting and drama, investors were turning away, developers were leaving – and much of the volume on the Run network was from a narrow set of customers who themselves looked shaky.

In the summer of 2022 the team got together in the Cotswolds in the UK and hatched an ambitious plan. We would take the essence of Run – the object model, the developer experience – and build our own layer-one blockchain that was intuitive, easy to work with, and could scale globally with fast, cheap transactions.

The pivot was always going to be a long shot. Building a blockchain from the ground up is not trivial, and the risk of running out of funding before we got there was high without further investment. But the alternative was bleak too, and the team unanimously agreed on the plan. We rolled up our sleeves and the Aldea journey began.

Team dynamics and my role

The Aldea team evolved slightly over time, but at the start it consisted of five people. Myself, Brenton, and another Bitcoin old-timer Miguel Duarte (who previously worked on the Money Button wallet) were the core experienced developers with a blockchain background. We also had a very talented designer, Ani, and a front-end developer, Ariel.

It was a small team, distributed over three continents, but we had something rare: that magical feeling when individual strengths perfectly complement each other, and there’s a mutual sense of trust, warmth, and fondness.

Myself, Brenton, and Miguel spent a lot of time in what we called our deep dives – meetings where we zoomed in on specific technical challenges and design choices. No one individual ever had all the answers, but together we thrashed things out, always making space for each other’s perspectives without judgement. After making decisions, we would often end the meeting with “let’s review this tomorrow”, allowing space for ideas to evolve and improve. The dynamic worked, and I’m proud of many of the key design choices we made.

Individually we each took ownership of different areas. Miguel created our initial VM and TypeScript devnet node, and worked with Brenton on the Rust-based mainnet node. Meanwhile, I took on responsibility for the compiler, CLI, and TypeScript SDK. This let me focus on the complete developer experience – I wasn’t just writing code, I was defining what it would feel like to work with and build on Aldea. It was the kind of ownership and creative freedom that makes you deeply invested in the work.

I also worked closely with Ani. Together we created the website, block explorer, documentation site, and a web-based interactive tutorial that ran our devnet and CLI inside a browser – lowering the barrier to entry for developers wanting to try Aldea.

The technical journey

Aldea gave us a blank sheet of paper: every technical challenge, design choice, and trade-off was on the table. At the same time, we wanted to bring Run’s DNA with us – keeping the essence of what made Run a joy to work with.

Establishing the foundation: AssemblyScript

One thing we knew users loved about Run was that creating tokens and interactive objects was just JavaScript. We wanted to retain that low barrier to entry, but we also knew that Run’s execution model – everything evaluated inside a single-threaded Node.js process – was a bottleneck that would prevent the kind of scale we were aiming for (millions of transactions per second).

We reviewed several fast embeddable JavaScript runtimes, but I suggested the team take a look at AssemblyScript – a TypeScript variant that compiles to WebAssembly. AssemblyScript offered us an almost like-for-like JavaScript standard library and a stronger type system with runtime guarantees.

While AssemblyScript introduced a few new concepts, it was close enough to JavaScript to maintain a low barrier to entry. It worked with standard TypeScript dev tooling and language servers, and it gave us a fast, embeddable WASM runtime. The team was immediately on board – it felt right from the start, and it was a big decision we were able to make quickly.

Defining the programming model

With AssemblyScript chosen, we faced a broader question: what kind of code could be deployed and executed on Aldea? This wasn’t purely technical – it would define what it felt like to build on Aldea.

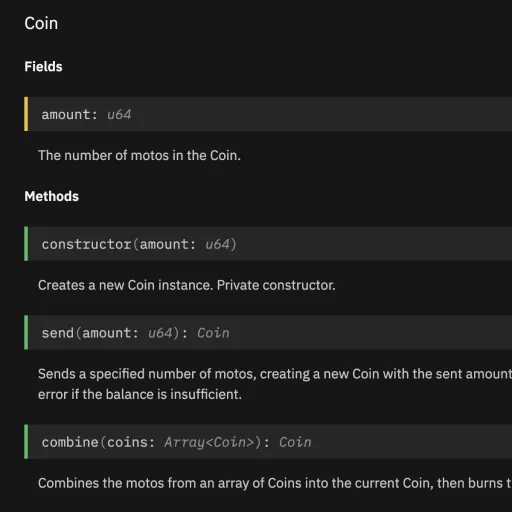

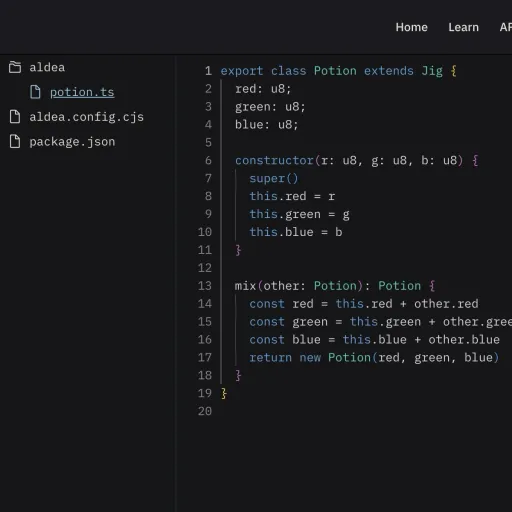

The core concept was objects – specifically, interactive objects that lived on-chain. We called these “Jigs” (a term inherited from Run). A Jig was a class instance that persisted on the blockchain, that had state, and could be owned, transferred, updated, and interacted with.

import { Armour } from 'pkg://13362514c449b2d3715f0c10f6e5e0aa409f863677d783ee57614ca4cf43a1b0';

import { PowerUp } from 'pkg://5be26813578740b964cf5aae575c0959bbb7ec444098f2a1af130015b0a05ab5';

export class Sword extends Jig {

public stregth: u8 = 1;

levelUp(powerUp: PowerUp): void {

this.strength += powerUp.consume();

}

strike(target: Armour): void {

target.recieveStrike(this);

this.strength -= 1;

}

}With Jigs as our starting point, and a rich and flexible programming language at our disposal, we had to decide what other kinds of code made sense in a blockchain context, and what didn’t. Over time, we settled on allowing packages that could contain the following types of code:

- Jig classes – the main event. Classes extending a built-in Jig base class, with special properties like an output ID, origin and location pointers, and a lock mechanism for ownership/control.

- Functions – pure static functions. Since Jigs were instances, we disallowed static methods on Jig classes for clarity. Instead, a package could export regular functions to serve as static code.

- Interfaces – to promote composability. For example, we defined a

Fungibleinterface as a standard for implementing compatible fungible tokens. - Sidekick code – private internal code. Any classes that weren’t Jigs, or functions not exported from the package, existed as private helpers.

This model took time to figure out. We’d propose something, sleep on it, refine it, and repeat. Gradually it shaped into a model that was both powerful and intuitive – familiar to any object-oriented programmer, but purpose-built for blockchain.

Ensuring determinism and safety

A blockchain environment demands deterministic execution: running the same code with the same input must always yield the same result. We also had to make sure Aldea was safe – that user code couldn’t crash the host or escape the sandbox.

From our experience with Run we knew that we had to remove all sources of entropy – for example Math.random() and new Date(). AssemblyScript also exposes several ways to directly access the raw WASM memory, which we had to ensure users couldn’t call.

Beyond that we had to think adversarially, and consider the weird and non-obvious ways a developer might break things – intentionally or otherwise.

For example, we had to prevent code from looping forever, and we couldn’t allow complex objects to be assigned in the root scope because they were mutable and a source of non-determinism.

Much of this work fell to the compiler, which enforced an extensive set of validation rules at compile time. We also had to get creative and implement ways for the VM to track and halt execution if a call wasn’t permitted or was taking too long.

The lock mechanism

One fundamental design choice we had to consider early on was how to handle control or ownership of Jigs. We tended to prefer the term “control” over “ownership”, as it reflected the mechanics, rather than legal concepts. Either way, we needed a mechanism to define when and how a Jig could be interacted with and updated.

One idea was to leave it up to users: locks could themselves be code that is deployed in packages, and we could let an ecosystem of lock types emerge. This flexibility was tempting, but it would have effectively made Jigs public by default, putting the onus on developers to think about and manually implement locks for everything.

In the end, we felt most of the time people wouldn’t want to think too hard about this, and that a better experience was to provide a simple, first class lock mechanism built into Aldea. We settled on a model that supported three primary lock types:

- Address lock – A Jig is locked to an address (similar to a Bitcoin P2PKH script), and can be updated in a transaction containing a signature from the associated private key.

- Jig lock – A Jig is locked to another Jig, meaning only the parent Jig can update or call methods on the child Jig.

- Public lock – A Jig with a public lock can be interacted with by anyone. A traditional smart contract would look like this.

In practice, this covered the vast majority of use cases. For more specialised scenarios, developers could still implement bespoke lock logic and combine it with public Jigs.

Elegant composability

A rich programming language and an intuitive object model are useful, but the real magic appears when Jigs interact with other Jigs – when developers can import code from other packages and mix, extend, and build on each other’s work.

Pulling this off required tight coordination across the codebase. The CLI needed some package management features, so developers could “pull” other packages from Aldea into their local environment. Combined with some TypeScript trickery, this let us reliably infer the types of external packages both in development and at compile time.

At runtime, every method called on a Jig – whether defined in the same package or another – had to be checked against the lock rules. Essentially, the VM had to be involved in every call to any Jig that wasn’t the current context.

AssemblyScript doesn’t support JavaScript Proxy objects, so there was no easy way to intercept calls dynamically. Instead, the compiler dit a lot of “magic”, transforming code at compile time so calls were always routed through the VM.

This work didn’t happen overnight – it was an iterative process the unfolded as we built Aldea. But where we ended up was a perfectly familiar developer experience that just worked – powered by a lot of invisible machinery behind the scenes.

Transaction format

A blockchain is a deterministic state machine. On-chain code – Jigs, smart contracts, and so on – runs in a sealed box. The only way to interact with it is through transactions. Transactions are the input input mechanism – a list of instructions and associated data.

We leaned into this idea of a transaction as a list of instructions. Miguel designed a low-level, assembly-like format, and together we refined it down to a set of just 11 opcodes, and settled on BCS (Binary Canonical Serialisation) for encoding parameters.

// Loads an output by its ID

LOAD 0xC301A62EE9319201189CF1CC0C9DA03E0CEF12BC47A589F3EED7E268E0E5A5E9

// Calls a method on jig passing the encoded arguments

// 0 is the instruction reference of the target jig

// 2 is the index of the public method according to the Jig's ABI

// Params encoded with BCS

CALL 0 2 0x0568656C6C6F05776F726C64Although this was a much lower-level that the internal programming model, it meant transactions themselves could remain compact and fast to encode and decode. There was also a certain elegance to each transaction literally being a short “program” – a story told as a list of instructions.

Bringing it all together: Implementation

These design decisions – from AssemblyScript to locks to transaction formats – formed the blueprint for Aldea. But blueprints need to be built, and the act of implementing them constantly forced us revisit our assumptions and refine the design.

I was primarily responsible for the compiler – a critical piece of Aldea’s infrastructure and a significant undertaking. Our compiler wrapped around the AssemblyScript compiler, hooking into various stages of the compilation process. Alongside validating user code, it performed a lot of transformations – ensuring the VM was looped in on every method call, could follow the call stack, and could halt execution when needed.

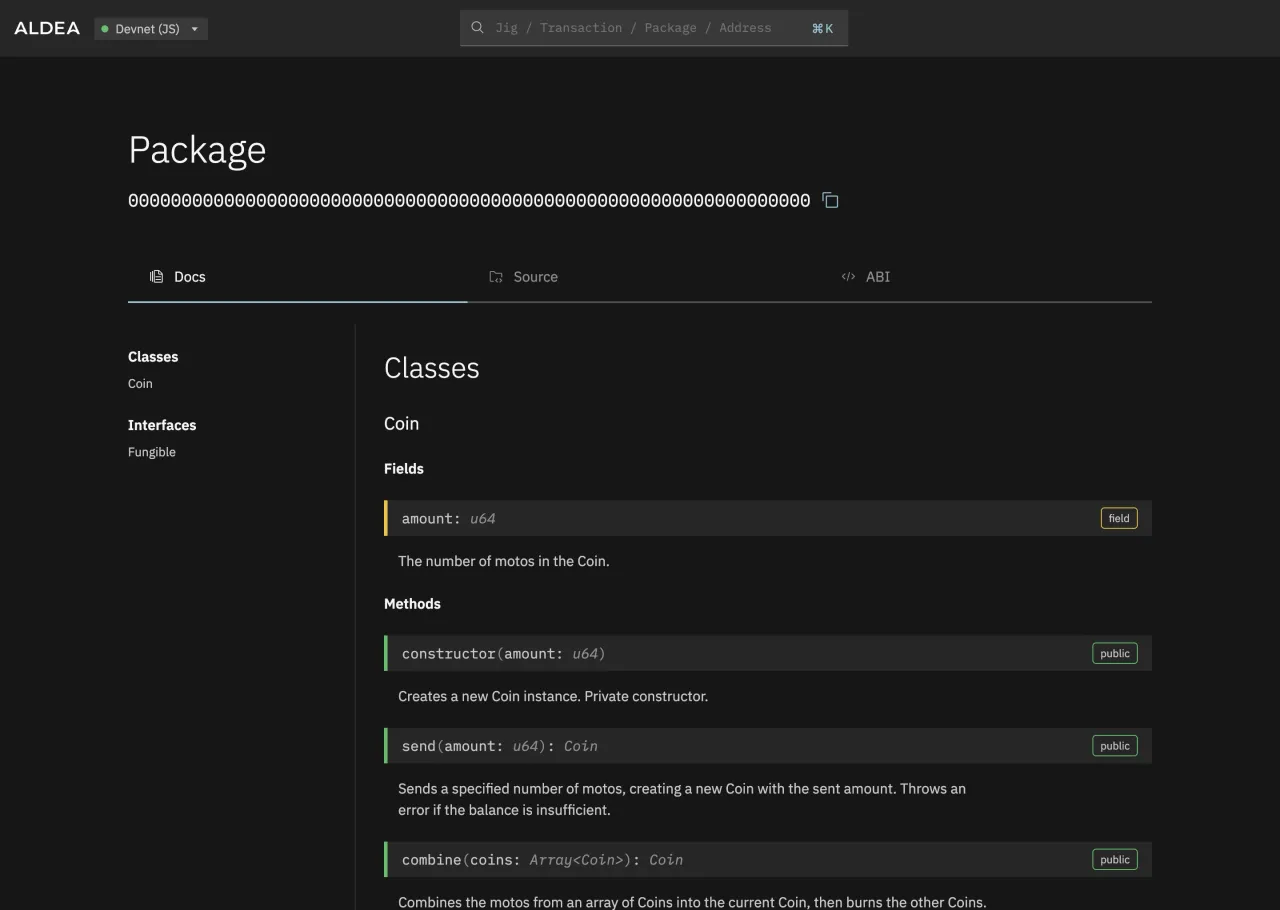

I also took on the TypeScript SDK. This package contained all the primitives and data structures for working with Aldea – transactions, instructions, outputs, packages, pointers, addresses, and more. In building the SDK, I wasn’t just implementing a spec, I was defining the spec itself, and how these core concepts would be represented and encoded on-chain.

Miguel led the VM and our TypeScript-based devnet node – a single-node developer environment for building on Aldea locally. Our work depended heavily on each other, so we collaborated closely. Meanwhile, Brenton led the Rust-based mainnet node and focussed on the scale and performance aspects of the design.

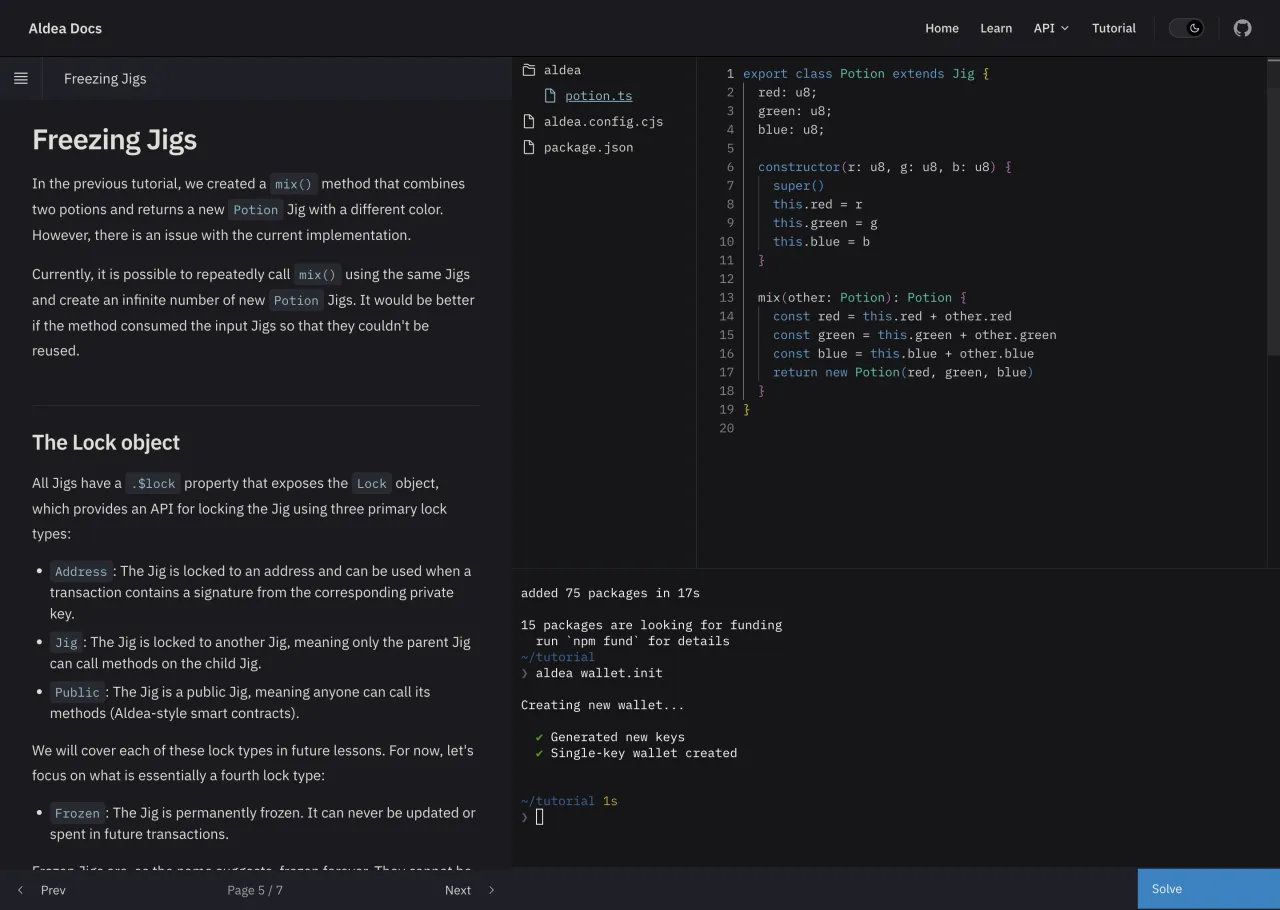

Working with Ani, I built the company website, block explorer, and our documentation site. One piece I’m particularly proud of is the interactive tutorial. Using WebContainers, we provided a complete development environment – including a running instance of our devnet node – inside a web browser. You could write code, compile packages, and deploy them to your devnet, all in a single tab. It was the purest expression of our “blockchain for everyone” philosophy: the barrier to entry was literally “open this page”.

What we achieved (and what we didn’t)

One hill I’m absolutely willing to die on is that we nailed the Aldea programming model. Jigs, packages, composability – it all felt right. The Aldea Computer could have justifiably claimed to be one of the most intuitive and developer-friendly blockchains on the market.

Nothing in software is ever truly finished, but the compiler, the devnet node and VM, the CLI, SDK, and developer tooling were all in a solid state and not far away from what you might call “version 1.0”. The team also made some good progress on the Rust-based mainnet node, with impressive transaction processing performance. But we still had some big, non-trivial problems ahead – tokenomics and consensus, to name a few. We were still months, if not another year, away from launch.

Unfortunately, we simply didn’t have that time. In the wake of the FTX collapse, and with AI emerging as a more compelling investment story, it was a brutal period for blockchain startups. Brenton, our CEO, fought hard and kept pitching. Our existing investors helped keep the wheels turning, but they also increasingly intervened, pushing us to focus on partnerships over development. This felt less like a strategy and more like a last, frantic wave of the arms before slipping under the water.

When the hoped-for partnerships failed to materialise, we knew our time was up. It’s a testament to the team that in those final few weeks, we all kept coding, trying to leave behind something we could show people and be proud of. All of our code is open source and still available to read and learn from, and our block explorer, documentation, and interactive tutorial remain live and functional today. In the days before Christmas 2023, we said some emotional goodbyes, and the Aldea journey was over.

Reflections: What I learnt

What we lacked

Looking back, I recognise that as a team we had gaps and made our share of mistakes. At times we lacked ruthlessness in decision-making, and we sometimes committed time and energy to efforts that, in hindsight, gave little in return.

In particular, we made performance and scale a major part of our story and felt that, for the story to be credible, we needed to demonstrate it. In truth, all work proving a scaling model was premature. A live blockchain that only handles 10 transactions per second still beats a blockchain that doesn’t exist beyond promises to scale to millions. Launching something, however limited, should clearly have been prioritised over scaling models and transaction processing simulations.

We also spent too long in “stealth mode”. Some on the team saw this as a strategic choice; I was more sceptical. It’s never too early to start generating interest, and we should have made it a priority to talk about our design and the choices we were making – to show to the world that we were building something interesting.

The biggest question is whether this was even the right pivot? We were in a tricky spot: big block Bitcoin was a mess and, looking at how things have played out since, sticking with Run wouldn’t have left us any better off. We couldn’t have known that FTX was about to blow up, or that AI was about to burst onto the scene and soak up most of the available VC money. But building our own chain from scratch was such an ambitious undertaking that it was never going to be possible without additional investment. I do wonder whether there was a simpler, more lightweight direction that we could have focussed this talented team towards.

What I believe

I’ve long felt that, over time, adoption will converge on a small number of winning blockchains, and most others will fade away. Indeed, that process may already be under way.

Among the big chains, none has truly prioritised accessibility, ease of use, and a low barrier to entry. Instead, the cypherpunk ideology and crypto purism I mentioned earlier still sets the tone for much of the space.

Philosophically, Aldea’s closest comparison is Sui – an offshoot of Meta’s abandoned Diem project. Sui uses the Move language – definitely less accessible than AssemblyScript – but its model is object-oriented, and much of its positioning emphasises the developer and user experience.

When you look closely at Sui, a lot of the internal design concepts are strikingly similar. Run predates Sui by years, so we can hold our heads up as genuine innovators. Seeing the Sui team independently hit the same design challenges and land on a very similar model is a strong validation of our thinking.

The human element

Despite the overall failure, my time building Aldea will remain one of the most enjoyable and fulfilling periods of my professional life. This is in no small part due to the amazing team.

We clicked. Our strengths and knowledge areas complemented each other. We trusted one another, helped each other when needed, and – crucially – we enjoyed the work. We were all sad when it ended, but I think it says a lot that we kept building even when we knew the end was close.

Aldea will remain – in our hearts at least – the greatest blockchain no one has ever heard of.